Reported by Joe Miller in New York and James Kynge

In January 2021, US Drug Enforcement Administration agents watched a man drop off a large white bag with “Happy Birthday” written on the side at an office complex in Downey, California. It contained $226,000 in cash.

Three months later they witnessed the same man leave a Fruity Pebbles cereal box full of almost $60,000 in cash at a house in Temple City, California.

The DEA initially thought the cash deliveries were the routine result of the soaring sales of fentanyl in the US. But during the course of their investigation, they suspected the drop-offs were also part of a sophisticated and growing form of illicit finance that involves so-called Chinese underground banks and the Mexican drugs cartels.

In an indictment unveiled in a California court last week that provides an unprecedented insight into the allegedly evolving global network, prosecutors accused Edgar Martinez-Reyes, who was present at the two cash drop-offs, and a group that included nine Chinese nationals of laundering $50mn for the Sinaloa cartel in Mexico.

Martinez-Reyes, a Mexican national who lives in Los Angeles, has pleaded not guilty, as have the other 11 defendants who have so far been arraigned. The case is likely to go to trial.

For the law enforcement agencies grappling with the fentanyl crisis, the indictment represents anything but an isolated incident. They claim the alleged offences are part of a process where over the past decade Chinese organised crime groups have moved in to launder the earnings of the Mexican cartels.

The money laundering groups are made up of networks of Chinese nationals living in the US and Mexico as well as individuals in China. As fentanyl revenues have surged over the past few years, the officials say, their relationship with the Mexican cartels has expanded dramatically.

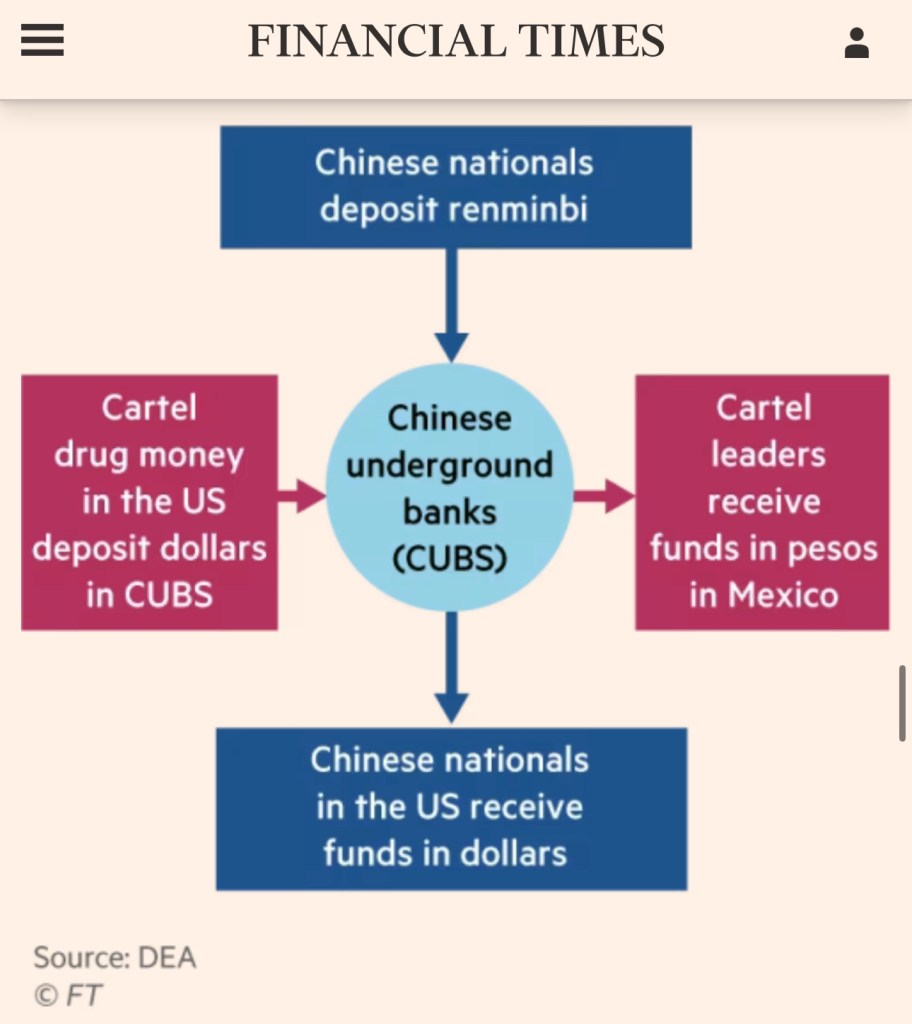

The underground banks operate largely by selling the cartels’ dollars to wealthy Chinese who, alarmed at the political tightening under Chinese leader Xi Jinping, are looking to circumvent capital controls and transfer their money out of the country.

In essence, the officials claim, a new global money laundering network has evolved that marries two powerful financial forces — the huge stockpiles of cash being accumulated by the Mexican drugs cartels from selling drugs in the US, and the rapidly growing volumes of capital seeking an escape route from China.

While the huge profits being made from fentanyl have been widely publicised, the other side of the money laundering operation — the demand for dollars from Chinese individuals — is less well understood.

Capital flight from China is by no means a new phenomenon but in recent years the scale of these transfers has surged, according to both Chinese officials and analysts who track China’s international remittances.

“The levels of capital flight in the past three years have been quite alarming,” says one senior Chinese official, who declined to be identified and who says that a lot of billionaires and multimillionaires are trying to leave China and take their money with them.

“Some wealthy private entrepreneurs are losing confidence in China’s future. They feel unsafe so they are finding ways to get their money out.”

A regulatory crackdown on private enterprises that lasted for about two years from 2020, the ceaseless investigations into individual corruption and a sense that China’s military build-up could one day lead to conflict are prompting China’s wealthy to find exit routes for their capital.

In addition, some wealthy Chinese say that Xi appears ideologically opposed to personal wealth. His “common prosperity” policy, invoked in 2021, heralds what many believe will be a multi-year programme to redistribute wealth from the haves to the have-nots.

David Lesperance, a tax and immigration adviser based in Gibraltar, says the exodus of wealthy Chinese eclipses anything he has seen in more than 30 years.

“The last two years have seen the biggest exodus of my ultra-high net worth Chinese clients in over three decades,” says Lesperance.

Calculating the extent of capital flight from China is not straightforward. It requires forensic analysis of China’s balance of payments data to work out how much money is leaving the country through informal or illicit channels.

Brad Setser, a former US Treasury official and an expert on global capital flows at the Council on Foreign Relations, a US think-tank, estimates that as of the first quarter of this year, private capital flight from China was running at an annualised rate of about $516bn. It was even higher in the third quarter of 2022 when it hit nearly $738bn.

These levels are well above outflows in the last quarter of 2019 — before the pandemic struck early in 2020 — which were taking place at an annualised rate of $94bn.

Such levels of capital outflow are huge; they mean that a chunk of money roughly equivalent in size to Norway’s entire gross domestic product is set to depart for foreign shores this year.

“A lot of Chinese residents no longer believe that China’s economic trajectory is clearly positive, and thus no longer necessarily want to hold a large share of their wealth in China,” says Setser. “As a result, many are looking to find ways to move funds abroad, even though that is technically hard for many average Chinese residents.”

A myriad different ruses are deployed to spirit funds out of China. While experts and law enforcement officials believe the global networks of underground banks are the most common route, other methods involve over-invoicing for imports, using cryptocurrencies or charging payment for non-existent services overseas.

Read full report: https://www.ft.com/content/acaf6a57-4c3b-4f1c-89c4-c70d683a6619